|

Part 2 of 2; you can find Part 1 here. Disclaimer: The following is based on my experiences and observations at about a dozen hospitals across the country. While I feel like it generally applies to the hospital experience (including some hospitals with glistening and lofty reputations for customer service and/or academic prowess), I can’t say it applies to every or even most hospitals out there. And again, just to be clear, for the hospital staff who have and will care for me: Nurses are awesome, and none of this is their fault. 3. Your room will be squeaky clean when you arrive, and will be kept that way I imagined a beleaguered but prideful cleaning crew dousing surfaces in bleach water multiple times a day, scrubbing every C. diff- and MRSA-tainted inch. In my experience, hospital rooms are cleaned less thoroughly than many hotel rooms. On my first day in one room, I found a bloody streak in the shower, brownish spatters on the floor, dead flies in corners. And you can be sure it’s not getting any cleaner over the course of your stay – it basically consists of a quick mop-swipe of the floor and emptying of your trash. If there’s a sample-collection “hat” or two in the toilet (which there will be), you can be sure that the custodians won’t get anywhere near it (and the LPN nurse won’t replace it with a new one either, unless you ask). The LPN nurses are actually pretty good about changing bed linens regularly, and I recommend doing this as much as possible, but it can take like 20 minutes and you’re stranded in your gown in some stained upholstered chair soaking your gown with Death Row sweat and trying to wait to vomit in semi-private. 4. The nurses will respond as soon as you call them Nurses are awesome, and they can make or break your hospital experience. But they work 12-hour shifts, often without a true lunch break, and are always slammed with too many patients. So they likely won’t be able to refill your water jug right away, or help you to the bathroom right away, or do anything right away but save your life. Which is what really matters. So if at ALL possible, try to always have a friend or family member with you to do these little comfort measures for you. And know that you’ll do the same for that person if/when they need you to. 5. Things will make sense You endured a visceral trauma while unconscious. You will probably never see a video of what happened during surgery (I have seen a video of someone else having my same surgery – it’s a disturbing mix of intriguing, soothing, and disturbing). But your body knows. Things were pulled out and apart, sliced and Frankenstein’s-Monstered back together. And this disconnect between what your body knows and what your brain knows can feel a little weird. You never saw or heard or felt any of it while it happened (hopefully), but you know it did. But be prepared to feel disoriented and a little scared and confused about what just happened to your body. Even if you know it was the right thing to do, and your surgeon has walked you through what was done step-by-step, it still doesn't feel quite right, like you flip through the pages of the last week of the book of your life and one page is blank. But that feeling does abate slowly, especially as you get to leave the hospital and return to familiar surroundings. 6. You'll start feeling better really soon and can get back to work/school/housework Once you come off the pain meds and start preparing to go home, it can start to hit you – this is a lot harder than I thought it would be. Maybe you won’t feel this way, and you will feel great soon. Or maybe you had to have the surgery because of a blockage from inflammation and malformation (like me), but the surgery introduced a whole new set of symptoms that then have to be contended with. And that completely sucks. Because everyone wants to ride out of the hospital on a parade float, with the princess wave that says, “I did it, I’m a winner, I made it through!” And it’s a pretty big downer to have to tell people, “I mean, yeah, I guess I’m better than I was a month ago, but I’m not great like some doctors said I might be. I’m really tired still, and my stomach is huge and my farts smell different and I still can’t eat lettuce.” But that doesn’t mean you won’t feel better, ever. I would just say, whatever recovery time your doctor tells you, that’s your stay-at-home recovery time, not your back-to-normal recovery time. And don’t take advice from doctors or other crazily driven and ambitious and un-sick people about when to return to work or school. These people will tell you that you can totally start grad school in two weeks post-surgery. These people are probably wrong. Ask someone who has actually had the surgery before, who is also a reasonable human being who gets 8+ hours of sleep and doesn’t run triathlons. And when you first return home, don’t be like me. Don’t try to secure a graduate TA position and respond to your well-wishers' emails and read a book about neuroscience. Decide ahead of time that your first week will be a stream of streaming TV. Ooh, and hire a maid service in advance for the day before planned discharge, so that at least your home is as spotless as your hospital room should've been. What other false surgery expectations did you have? Was your hospital room actually spotless? Let me know @katiefmclendon

Kermit's during-surgery expectations were way off. Screenshot from muppet.wikia.com Disclaimer: The following is based on my experiences and observations at about a dozen hospitals across the country. While I feel like it generally applies to the hospital experience (including some hospitals with glistening and lofty reputations for customer service and/or academic prowess), I can’t say it applies to every or even most hospitals out there. And just to be clear, for the hospital staff who have and will care for me: Nurses are awesome, and none of this is their fault. 1. You'll at least get tons of sleep and rest and reading time, and get to be drugged up the whole time! No, you won’t, and here’s why: You have to prepare for leaving the hospital almost as soon as you leave surgery. Like a prisoner’s parole hearing, there are milestones you must meet to prove to the doctors that you’re ready for release. This means doing regular slothy laps down the hallway with your stupid IV pole that rolls like the worst grocery cart you’ve ever pushed; eating three “meals” (broths) a day; and generally seeming like you’re gaining strength. If you had an intestinal resection, the milestones include farting, eating solid food, and not gushing blood out of your butt. Staff members are constantly in your room (except when your IV pole is beeping at 3 am, or you want ice water). Someone is always coming in to wake you up and check on you at shift change, or give you your meds, or finally reset your beeping IV machine. Especially soul-crushing is when they wake you to take blood at 3 am so labs are back for the doctor’s morning rounds. Which start at like 6 am, so heads up. Doctors want to get you out of the way before their office visits and surgeries. The golden slow hours of sleep-grabbing tend to be 3 pm to 5 pm, 11 pm to 2 am, and 4 am to 6 am. Much how they tell new moms to sleep whenever the baby’s sleeping, nab all the naps you can while you're left alone. But again, this is not reliable. Don’t worry, you’ll sleep again someday. Make it clear that everyone who plans to visit should come at the beginning of your hospital stay. Much more on family and friends in a minute, but your visitors will just show up at the hospital whenever, so don’t fret about having a schedule or point of contact for people to obey. I had in my head that there’d be a spreadsheet where people would sign up for 20-minute time slots when I was less likely to be sleeping, eating or farting. It turns out, people treat it like a wake – we know she’s not going anywhere, so I’ll drop in with some flowers and food whenever. And this is appropriate, because there is NEVER a consistent good time of day for people to visit (more soon on the best time of your stay as a whole for people to visit). You also have to start coming off of IV narcotic painkillers almost as soon as you start them. And withdrawal is a real bitch. Not only are these drugs extremely convenient and fun, they’re of course horribly addictive and life-destroying and should be used rarely and not for longer than necessary. So your body and brain may cling to them more than you expected, much like a romance-novel heroine desperately clings to the leg of her brawny scoundrel as he callously abandons her for another. A heroine clinging to heroin. I had the best time clicking my IV pain med button – I figured out it would release a mini-dose every 9 minutes, and it became a game to try to wait just long enough till it would give me the juice and I would hear a cheerful little “ding!” Yes, addiction runs in my family. No one gets to go home with “Get Well Soon” balloons and an IV morphine drip. You transition to pills, but pills don’t really cut the pain the same way. And all the meds are extremely constipating anyway, which quickly becomes a huge problem once your gut is awake. The nurses are the pill gatekeepers, and they start to ask you obnoxious questions like, “Are you sure you really need a pain pill, or are you just asking because it's been four hours?” The IV button never said insensitive things like that. Take the pain pills as needed, but know the party is ending, and you don’t have to go home but you can’t stay here. (And know that if you successfully get them to extend your IV-pain-med time, you will be staying there -- you're extending your hospital stay by that same amount of time. No one gets to go home with “Get Well Soon” balloons and an IV morphine drip.) It’s best to catch a begrudging ride with some extra-strength acetaminophen ASAP, before things get too weird and sad and dangerous. (I was taunted by Muppet monsters popping out from under my hospital bed during one particularly rough withdrawal. When I went home, I kept having auditory hallucinations that our air vents were playing lullaby music.) As you might imagine, drug withdrawal does not help at all with sleep. What does help with sleep: eye masks, neck pillows, and sleep headphones playing soothing music or podcasts. You might get really itchy from the IV morphine, so the nurses might give you IV Benadryl, which will also knock you out fast. You’re not going to feel like any heavy reading, so leave the novels at home. Flipping through low-brow magazines, maybe. Streaming TV, possibly (don’t count on the skimpy hospital cable). Music and silly conversation and painkiller comas, definitely. 2. Your family, friends and co-workers will be on their best behavior, because they know you're sick! While sitting in the ER on a Friday night with a 103-degree fever, chills and stabbing abdominal pain, I was copied on an email from my (former) boss to one of my clients. My boss already knew I was in the ER for unexplained symptoms. She wrote: “Katie is sick today but I’m sure she’ll be back on Monday morning and can take care of this ASAP.” I was impressed with her certainty about a situation I found to be pretty unclear at the moment (and it turned out I wasn't back at work till the next Thursday, probably solely out of my body being spiteful about that email). I replied to the client, copying my boss as well as another co-worker who was actually sane, and she was happy to take care of the issue on my behalf. Sigh. I also had family members:

(Those three bullets pretty much condemned everyone in my family. Still love y'all! I'm not perfect either -- I didn't even come see some of you or send a card when you were in the hospital, so I suck more.) You will be a fun mess, who will be so hopped up on meds that you’ll be thrilled all these people are in one room with you and brought you presents! So, set clear expectations with your boss – “I am having a major surgery, and my doctor says if all goes well, I can aim for returning to teleworking on (date) and in-office work on (date), but she warned that I can't be sure until we see how the surgery goes and how quickly I'm recovering. But I promise to keep you regularly updated on my return as much as I am able. I apologize for any inconvenience, and thank you!” (You probably can leave off the apology, unless you’re Southern -- excessive passive-aggressive apologizing is kind of our thing.)

For family members, make it clear that everyone who plans to visit should come at the beginning of your hospital stay. This may seem counterintuitive: “But I’ll be a mess! I’ll be all drugged up!” Exactly. You will be a fun mess, who will be so hopped up on meds that you’ll be thrilled all these people are in one room with you and brought you presents! Everything you say is hilarious and you are universally adored! Yay! And oh yeah, you survived the surgery you were so worried about! Yay again! You’ll even still be thinking how cool it is that you never have to get up and pee or crap, because you conveniently still have a catheter and your bowels aren’t “awake” yet. And everyone’s being so nice! Whee! Enjoy the visitors and the euphoria and the Barbie-like lack of bodily excretions in these early post-op days, but be prepared to gear up to go home and get some much anticipated sleep. Next month, I’ll talk about four other big false surgery beliefs, including the condition of your hospital room, what happens when you press the call button, and how you’ll feel mentally and physically. From Drag Me To Hell IMDb.com page All she has to do is get rid of that button. (If you haven’t seen Sam Raimi’s movie Drag Me To Hell, I won’t give away the ending, but spoiler alert about some plot points.) In Drag Me To Hell, a young woman working at a bank is trying to prove to her boss that she can be as ruthless as her colleagues, to earn a much-needed promotion. This results in her being unkind to a tiny old woman who begs her for a little more time to catch up on her mortgage payments. Long story short, the old lady has special powers and while attacking her late one night, pulls a button off of her coat and curses it. Through a series of events, the protagonist discovers the only way to rid herself of the curse is to pass it along to someone else — by giving them this particular cursed button the woman pulled off her coat. As happens with IBD, I’ve been flaring to some degree for most of the past six months. At first, it was probably exhaustion and adventurous food choices from my awesome trip overseas. Then, I got C. diff somehow over the holidays. Then … well, now is then, and I don’t really know. Was it the anti-C. diff antibiotics? The new probiotics? The Kit Kat bar I took a tiny niblet of last week? The exhaustion from unsuccessfully attempting to ascend a ninja-course warped wall about 25 times? The pollen now coating every surface everywhere always? Just my genetics? Bad luck? That time in second grade I wrote that mean note to my classmate and was too scared to admit to it when I got caught? Something else? Was it the antibiotics? The probiotics? The Kit Kat bar I took a tiny niblet of? Just my genetics? That time in second grade I wrote that mean note to my classmate and was too scared to admit it ? I feel like there’s a cursed button somewhere that some horrible person gave me, but I can’t find it, despite years and $$$$ of searching. Or maybe there was a curse, but it’s gone but already did its damage and now I’m just living in the ruins. Or lots of tiny buttons, and I’ve found a few but have one (or 30) more left to find. It’d be pretty great to just know whether I should be looking for anything at all, let alone actually know where to look and what to do when I find it. But if I can’t even find it, it’s hard to be able to give it away (not that I would do this — I guess maybe to a murderer on death row, or a mean-spirited chicken about to be slaughtered anyway). From Drag Me To Hell IMDb.com page It’s not to say it hasn’t been hugely helpful, this button quest I’ve been on for a few years now. I’m significantly healthier, and I’m pretty sure it has a lot to do with diet and sleep and being done with grad school. But healthier, not healthy. Which, again, could be fine if I knew there was no other better, healthiest-possible self out there waiting for me to pass the baton to her for the remainder of the race. And I’m not aiming for a marathon or even a 5k, or to come off my IBD medications and stop going to the doctor like 4 times a week. I really would just like to not have everything suddenly sometimes inexplicably unravel into demonic diarrhea and constipation and aches and exhaustion and cramps and infections and rashes and all the things you probably have or have had too. If I’m spending all this time and money, I’d like a little better ROI (return on investment), or even just CSSOISBM (confirmation some sort of investment should be made). Really, I’m just aiming to shrink the button, as it was the size of a dinner plate and now it’s down to something you might see on a clown costume. Instead, I find a loose thread and I start following it upward to the source, tugging and sometimes regretting having started the whole thing because now there’s a big hole left that I’ll have to patch. Or I think I found the button and even maybe handed it off to someone somehow for a few weeks or months, but then look down and see it sewn to my shirt again. Really, I’m just aiming to shrink the button, as it was the size of a dinner plate and now it’s down to something you might see on a clown costume. But I am grateful for how far I’ve come with the help of many people, and a horror-movie analogy like this does help give me perspective. Unlike the cursed loan officer in Drag Me To Hell, I’m by far not alone in this dilemma, things have gotten generally better instead of increasingly worse, and the only unreasonable sacrifice I’ve been asked to make lately is dessert.

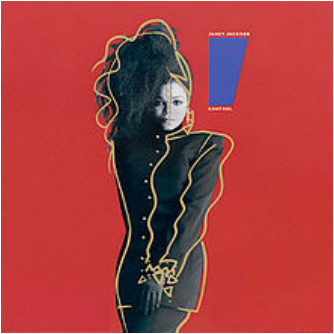

The cover of Janet Jackson's Control album, courtesy Wikipedia. I was the one calling family last week. I went to a quiet room and planned my first line of my first call. It wasn’t a death call, thankfully. But I was telling them that our fellow loved one had fallen seriously ill, maybe. She was in the ER. The recipient of this first call was very concerned about our loved one’s well-being, asking panicky questions in rapid succession, but then paused and seemed a little disoriented. “Well … are you OK?” the recipient asked. Apparently, me being the person who’s NOT in the hospital was a little hard to adjust to for some. It was weird for me, too. I've had more medical emergencies than some 80-year-olds, but I’ve never been in this role – being a “rock” that people can lean on for reassurance and info, starting the phone tree of alerts to family, making the calls that start with, “Hey, so everything and everyone is OK, but (as you may have suspected, that's not actually true, I'm just telling you that no one is dead yet)." It was disorienting for me, but beyond that, it was also uncomfortable, for a few reasons. First of all, I had to invent the wheel, because I’ve never done these bad news/reassurance calls to family. Usually, I’m calling a designated family member with an IV in my arm and a nurse checking my blood pressure, asking that person to make the rounds on my behalf since my hands/arms are a bit full at the moment. However, I do have some experience with snarky critiques of the medical system, so I made sure to put these to good use when my loved one was live-blogging her experiences via text. Also, it was a little sad but oddly flattering to see what those who loved me must’ve been feeling and saying when they heard about my worst flares. I mean, I don’t wish emotional pain onto my relatives, but would I want the alternative? “Oh, Katie’s in the hospital? Huh. Well, uh, let me know when she's ... not?” I am fine with it falling short of a melodramatic clutching of the chest and collapse to the floor, despite how extremely flattering and thoughtful that would be. But the weirdest part was the loss of a sense of control. And I did not like it. It’s not like I wanted to be in the ER instead of my loved one, just so I could control things. Right? It would’ve helped if I could’ve actually at least been there with this family member, so I could feel useful by bringing a hospital emergency kit (magazines, eye mask, sleep headphones and cell phone charger) and answer questions in real time. But honestly, I just wanted for it to be me. Me with the huge medical history and track record, and knowing what I’ve told the doctor already and still need to tell the doctor. Me deciding what to change in my lifestyle after I’m discharged, and what I can let fall by the wayside. Not having to wonder whether I’m sending the wrong advice, or might wake her up if I text at noon because she was probably woken up repeatedly all night and needs a nap. Or whether I should send a custom get-well-soon gift basket, despite her not even having a hospital room number yet and possibly getting discharged any minute. And I could see everyone around me grasping for bits of the steering wheel – Googling risk factors to mention to the doctor and asking whether Our Beloved One had told the doctor about hers, wanting to fly there right away to be at bedside. Anything we can do to help from here? Not really, unfortunately. Yeah. But the truth is that we don’t have that much more control when it’s us in the emergency room. That’s why we’re there – we don’t know what the hell is going on, and it seems serious. Or even if it doesn’t seem that serious, we know that with our medical history, it might still end up serious anyway. We tell ourselves we have more power over ourselves than we do, first of all because if we didn’t, then it would make a lot of our big life decisions seem irrelevant, and we’re always buzzing around fretting over decisions. We plan on when to have kids despite the fact that about half of pregnancies are unintended. We eat a certain diet and don’t smoke so that we won’t get heart disease or lung cancer. Except some of us do anyway no matter what. And we never have control over the lives of those we love, hospitalized or not.

In the hospital, I tell myself that without my all-clear, my body won’t be able to die. I actually believe this, despite knowing otherwise. It’s kind of perpetuated in books and movies and TV, too – the idea of telling terminally ill people that it’s OK to let go (and then they shall decide whether to release their grip on the living world or not). But whether we’re in the ICU or at home, with IBD we don’t really know how much control we have at any given point. Did that meal not go well because it was too big, or too late at night, or because I was stressed when I ate it? Or ate too quickly, or was sleep-deprived, or laughed or cried too hard with a full stomach, or because of some secret cheese somewhere in it? Who the hell knows. But you can’t just give up, either, because all those things – the meals and the medications, the sleep and the stress – do matter and are ways to exercise the control you do have over how you feel. But trying to change those lifestyle factors for someone else is awkward and annoying, like pulling strings on a marionette that keep getting snarled together. Plus, the marionette is its own being (in this analogy, I guess I'm going with it being a still-stringed Pinocchio) and is slapping you away, like, “How did you even get those? I've got this, stop it!” And I do have plenty of my own strings to untangle and pull, they’re just brittle and knotted and infuriating. And I’m less concerned about my own performance than about having everyone still around to fret and hover and call each other during my next visit to the hospital. |

Gut Check

Archives

January 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed