|

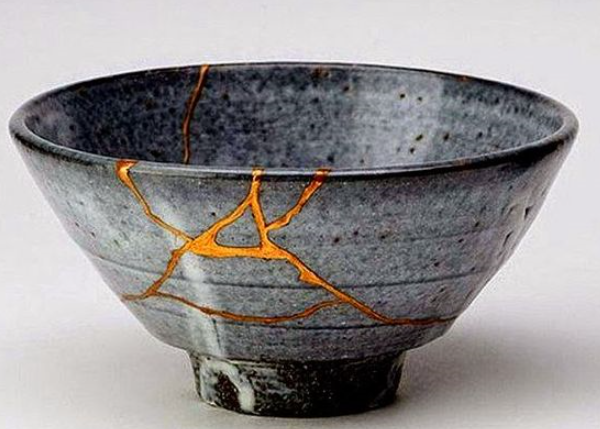

Screenshot from Pinterest Kintsugi is a Japanese word and concept, and one of those foreign words (like Denmark's hygge) that doesn’t have an English equivalent. But kintsugi as a broader concept can be roughly translated as a method of fixing something that makes the repair part of its beauty. Instead of taking a beheaded porcelain cherub and painstakingly dabbing just enough transparent glue to invisibly reattach the head and seal the wound, someone following the literal practice of kintsugi might (still painstakingly) use lacquer mixed with molten silver or gold to create a beautiful sealed crack that is meant to be noticed. (Or, riffing on kintsugi a little, maybe you’d use bright-red hot glue to christen your new zombie cherub into its afterlife. That’s probably what I’d do.) Mild spoiler alert: In the latest season of Amazon series “Man in the High Castle,” in anger about something unrelated, the Japanese trade minister broke a precious porcelain cup that belonged to his baby grandson. This rage and the words he had spoken caused a rift between this normally gentle man and the rest of his family, and the cracked cup became a symbol of this distance and loss of trust. He then decided to use kintsugi (giving the episode its title) to put the cup back together, creating an obvious but attractive fault line where the break had been, and the start of a new beginning with his family. Inherent to kintsugi is not pretending the past never happened. After something breaks, it’ll never go back to how it was, and it doesn’t mean it wasn’t a painful process or that everything’s all better now. Or that you don't regret what happened. Or that it was your destiny or for a greater good necessarily. Screenshot from Amazon's "Man in the High Castle" But the beauty that came from that negative experience--that argument, that scrape on your knee, that major surgery--would’ve never existed without the trauma that shaped it, and there’s not much left to do but give up or appreciate what’s left behind. You decide to take the shambles of what was and construct something different but wonderful, to move forward while not forgetting what happened. In fact, you’re drawing attention to the incident and how it changed you, or people around you, or everything. My biggest abdominal surgery, in 2009, was technically minimally invasive--the tiny laparoscopic incisions healed faster and better than I’d hoped, and what was left was just a handful of pale, barely puffy scars. You wouldn’t know to look at me that I lost 10 inches of intestine, a job, a year of school, and a crappy friend or two. It definitely cracked me, that surgery--I slept 11 hours each night, and awoke weepy and adrift each morning (well, afternoon). Should I have gone back to school right after having the surgery? Should I get this degree at all? Was I even smart enough to get this degree? Shouldn't I be feeling better by now? Should I be watching so many Lifetime movies? Was I going to go broke and have to get a job or go back to school before I was ready? Was it too soon to try to eat fruit again? Should I be showering more often? (No; maybe not; yes; no; probably not; yep; yes; definitely yes.) But you might notice now that I’ve gained more than 20 pounds (no need to mention it to me), the ability to eat insoluble fiber, a husband, a dog and jogging partner, a master’s degree related to health and a steady job using it. Would I have gained many of these things anyway without ever having had surgery or Crohn’s? Yes, I’m sure I would have. But I’m just as sure that I wouldn’t have all of them, and I wouldn’t be willing to spin a health roulette wheel to find out how it could all shake out differently. I tried at first to make the surgery mean I was CURED. Hallelujah! Despite the fact that surgery doesn’t do that for Crohn’s and I very well knew that. But I thought it might cure the worst parts of Crohn’s--the constant bathroom awareness, the relentless exhaustion, the hating of its limits on my big plans to join the Peace Corps and be an astronaut (not actually things I knew I wanted to do until I found out I couldn’t, but still). Screenshot from makezine And the part of having to just BE a sick person. When I went back to school, I told people I was forced to take time off because my appendix had to be removed. While that was technically true, it only had to come out because the appendix was attached to the scarred intestines that truly needed to come out. But the fudged appendicitis story was a quick, easy-to-relate-to tale, with a nice, neat “glad you’re feeling better now!” ending. It made sense for casual conversations with classmates, because no one really talks about chronic illness openly, not even in health-related degree programs (I found that almost everyone I spoke with one on one for any length of time had some personal health problem). I was even awarded a scholarship for people with IBD and dodged calls from the awarding organization, them leaving increasingly impatient voicemails asking for a bio to post on their website. (This was years before I had a blog sharing personal anatomical details with literally tens of people each month.) When animals get sick, their instincts tell them to hide their limp, or if they can’t, to hide themselves--or else get eaten. A dying pet cat may be found on a low bookshelf curled into a thinning ball, when it would actually likely appreciate some cautious petting on a warm lap. And sometimes these basic urges should be followed--to recuperate from the flu or a flare, you need to avoid exhausting, microbe-rich holiday parties and stream “Man in the High Castle” instead. But when you're feeling a little better, by just talking to someone else with Crohn's or participating in a small support group, you can take your horrible experience (having to drop out of school because you lost 30 pounds and couldn’t keep food down) and form it into useful or reassuring advice for someone who’s facing a similar decision right now, and vice versa. There’s a common wisdom around that “no one wants to hear about your personal problems or medical issues.” And that is so very true when you’re talking to your co-workers about an abscess on your butt. But imagine if you had that nasty abscess and had NO ONE to talk to about it. Imagine if no one had EVER written about ANY part of the gritty parts of Crohn’s, and then here you are with Crohn’s and good luck! Be sure to ask your doctor which brand of toilet paper to buy* when prepping for a colonoscopy, and how to cover up odors in a bathroom at a crowded house party. Thankfully, we have books and blogs sharing these non-medical details, and models taking the mystery and shame out of showing what it looks like to have scars or ostomy bags. As Carrie Fisher put it in a 2016 interview with NPR’s Terry Gross: “Oh, I think I do overshare … it's my way of trying to understand myself. I don't know. I get it out of my head. It creates community when you talk about private things and you can find other people that have the same things. “Otherwise, I don't know--I felt very lonely with some of the issues that I had or history that I had. And when I shared about it, I found that others had it, too.” And as Carrie Fisher also said (and fictional Trade Minister Tagomi demonstrated): “Take your broken heart, make it into art.”

* You probably already know which toilet paper you like. But in case you don't, for a colonoscopy or for any day, you want to not only focus on softness (not the one-ply institutional scratchy paper) but also on a brand that won't leave fluffy residue behind that will irritate your skin and just be generally gross. I avoid Cottonelle for this reason. With no official (or unofficial, yet) endorsement or compensation, I use Seventh Generation toilet paper and baby wipes. Charmin also swears by having this quality. |

Gut Check

Archives

January 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed