|

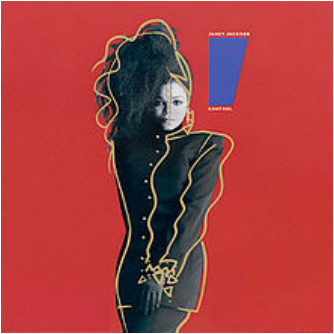

The cover of Janet Jackson's Control album, courtesy Wikipedia. I was the one calling family last week. I went to a quiet room and planned my first line of my first call. It wasn’t a death call, thankfully. But I was telling them that our fellow loved one had fallen seriously ill, maybe. She was in the ER. The recipient of this first call was very concerned about our loved one’s well-being, asking panicky questions in rapid succession, but then paused and seemed a little disoriented. “Well … are you OK?” the recipient asked. Apparently, me being the person who’s NOT in the hospital was a little hard to adjust to for some. It was weird for me, too. I've had more medical emergencies than some 80-year-olds, but I’ve never been in this role – being a “rock” that people can lean on for reassurance and info, starting the phone tree of alerts to family, making the calls that start with, “Hey, so everything and everyone is OK, but (as you may have suspected, that's not actually true, I'm just telling you that no one is dead yet)." It was disorienting for me, but beyond that, it was also uncomfortable, for a few reasons. First of all, I had to invent the wheel, because I’ve never done these bad news/reassurance calls to family. Usually, I’m calling a designated family member with an IV in my arm and a nurse checking my blood pressure, asking that person to make the rounds on my behalf since my hands/arms are a bit full at the moment. However, I do have some experience with snarky critiques of the medical system, so I made sure to put these to good use when my loved one was live-blogging her experiences via text. Also, it was a little sad but oddly flattering to see what those who loved me must’ve been feeling and saying when they heard about my worst flares. I mean, I don’t wish emotional pain onto my relatives, but would I want the alternative? “Oh, Katie’s in the hospital? Huh. Well, uh, let me know when she's ... not?” I am fine with it falling short of a melodramatic clutching of the chest and collapse to the floor, despite how extremely flattering and thoughtful that would be. But the weirdest part was the loss of a sense of control. And I did not like it. It’s not like I wanted to be in the ER instead of my loved one, just so I could control things. Right? It would’ve helped if I could’ve actually at least been there with this family member, so I could feel useful by bringing a hospital emergency kit (magazines, eye mask, sleep headphones and cell phone charger) and answer questions in real time. But honestly, I just wanted for it to be me. Me with the huge medical history and track record, and knowing what I’ve told the doctor already and still need to tell the doctor. Me deciding what to change in my lifestyle after I’m discharged, and what I can let fall by the wayside. Not having to wonder whether I’m sending the wrong advice, or might wake her up if I text at noon because she was probably woken up repeatedly all night and needs a nap. Or whether I should send a custom get-well-soon gift basket, despite her not even having a hospital room number yet and possibly getting discharged any minute. And I could see everyone around me grasping for bits of the steering wheel – Googling risk factors to mention to the doctor and asking whether Our Beloved One had told the doctor about hers, wanting to fly there right away to be at bedside. Anything we can do to help from here? Not really, unfortunately. Yeah. But the truth is that we don’t have that much more control when it’s us in the emergency room. That’s why we’re there – we don’t know what the hell is going on, and it seems serious. Or even if it doesn’t seem that serious, we know that with our medical history, it might still end up serious anyway. We tell ourselves we have more power over ourselves than we do, first of all because if we didn’t, then it would make a lot of our big life decisions seem irrelevant, and we’re always buzzing around fretting over decisions. We plan on when to have kids despite the fact that about half of pregnancies are unintended. We eat a certain diet and don’t smoke so that we won’t get heart disease or lung cancer. Except some of us do anyway no matter what. And we never have control over the lives of those we love, hospitalized or not.

In the hospital, I tell myself that without my all-clear, my body won’t be able to die. I actually believe this, despite knowing otherwise. It’s kind of perpetuated in books and movies and TV, too – the idea of telling terminally ill people that it’s OK to let go (and then they shall decide whether to release their grip on the living world or not). But whether we’re in the ICU or at home, with IBD we don’t really know how much control we have at any given point. Did that meal not go well because it was too big, or too late at night, or because I was stressed when I ate it? Or ate too quickly, or was sleep-deprived, or laughed or cried too hard with a full stomach, or because of some secret cheese somewhere in it? Who the hell knows. But you can’t just give up, either, because all those things – the meals and the medications, the sleep and the stress – do matter and are ways to exercise the control you do have over how you feel. But trying to change those lifestyle factors for someone else is awkward and annoying, like pulling strings on a marionette that keep getting snarled together. Plus, the marionette is its own being (in this analogy, I guess I'm going with it being a still-stringed Pinocchio) and is slapping you away, like, “How did you even get those? I've got this, stop it!” And I do have plenty of my own strings to untangle and pull, they’re just brittle and knotted and infuriating. And I’m less concerned about my own performance than about having everyone still around to fret and hover and call each other during my next visit to the hospital.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Gut Check

Archives

January 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed